You’ll need two to three hours to explore Sigiriya Rock Fortress. Visit in the early morning or late afternoon, when the crowds are less dense and the temperature is cooler.

The site divided into two sections: the rock itself, on whose summit Kassapa established his principal palace; and the area around the base of the rock, home to elaborate royal pleasure gardens, as well as various monastic remains pre-dating Kassapa’s era. The entire site is a compelling combination of wild nature and high artifice — exemplified by the delicate paintings of the Sigiriya damsels which cling to the rock’s rugged flanks. Interestingly, unlike Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, there’s no sign here of large-scale monasteries or religious structures — Kassapa’s Sigiriya appears to have been an almost entirely secular affair, perhaps a reflection of its unhallowed origins.

The Water Gardens

From the entrance, a wide and straight path arrows directly towards the Sigiriya Rock Fortress, following the line of an imaginary east—west axis, drawn straight through the rock, around which the whole city was planned. This entire side of the city is protected by a broad moat enclosed within two-tiered walls. Crossing the moat (which once enclosed the entire west-facing side of the complex), you enter the Water Gardens. The appearance of this area varies greatly according to how much rain has recently fallen, and in the dry season lack of water means that the gardens can be a little underwhelming. The first section comprises four pools set in a square; when full, they create a small island at their centre, connected by pathways to the surrounding gardens. The remains of pavilions can been seen in (the rectangular areas) to the north and south of the pools.

Beyond here is the small but elaborate Fountain Garden. Features here include a serpentining miniature “river” and limestone-bottomed channels and ponds, two of which preserve their ancient fountain sprinklers — these work on a simple pressure and gravity principle and still spurt out modest plumes of water after heavy rain. The whole complex offers a good example of the hydraulic sophistication achieved by the ancient Sinhalese in the dry zone: after almost 1500 years of disuse, all that was needed to restore the fountains to working order was to clear the water channels which feed them.

The Boulder Gardens and Terrace Gardens

Beyond the Water Gardens the main path begins to climb up through the very different Boulder Gardens, constructed out of the huge boulders which lie nimbled around the foot of the rock, and offering a naturalistic wildness very different from the neat symmetries of the Water Gardens. Many of the boulders are notched with lines of holes — they look rather like rock-cut steps, but in fact they were used as footings to support the brick walls or timber frames of the numerous buildings which were built against or on top of the boulders – difficult to imagine now, although it must originally have made an extremely picturesque sight.

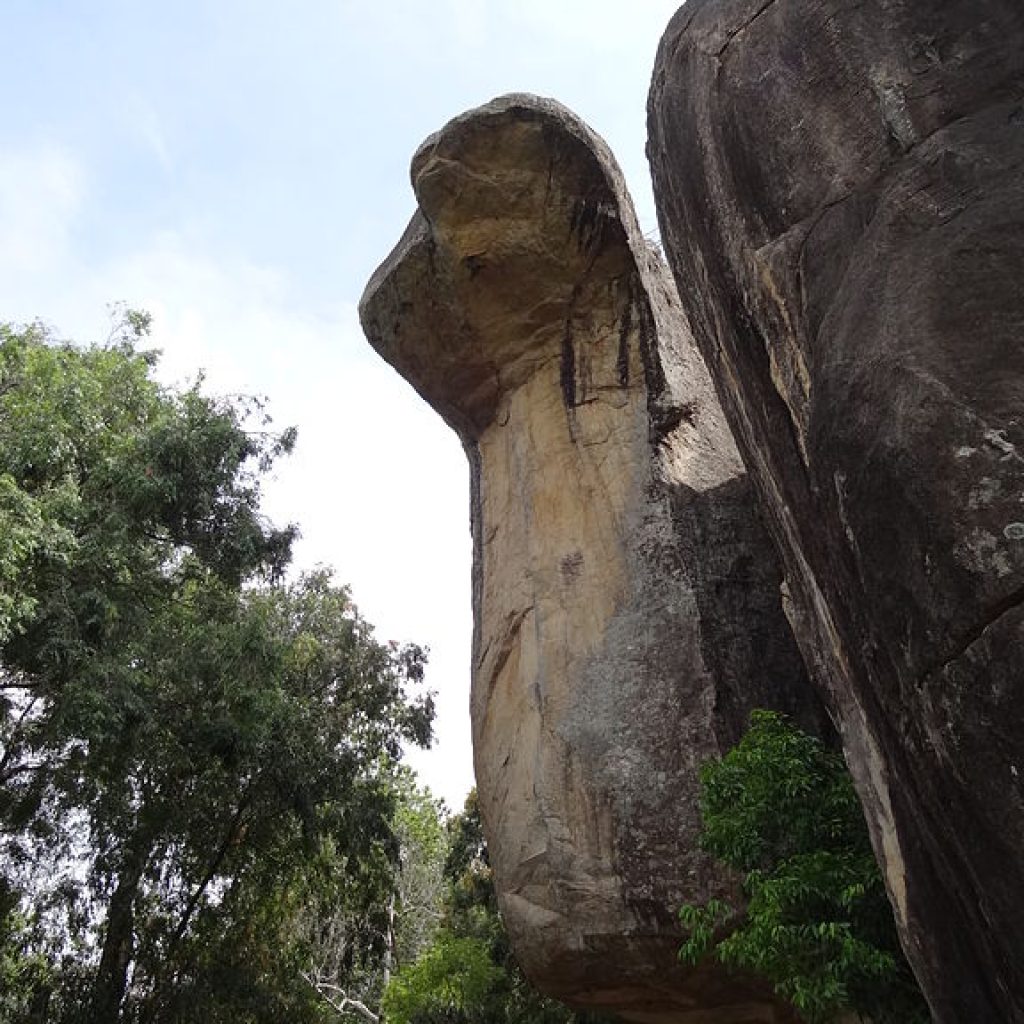

The gardens were also the centre of Sigiriya’s monastic activity before and after Kassapa: there are around twenty rock shelters hereabouts which were used by monks, some containing inscriptions dating from between the third century BC and the 6rst century AD. The caves would originally have been plastered and painted, and traces of this decoration can still be seen in a few places; you’ll also notice the dripstone ledges which were carved around the entrances to many of the caves to prevent water from running into them. The Deraniyagala Cave, just to the left of the path shortly after it begins to climb up through the gardens, has a well-preserved dripstone ledge and traces of old paintings. On the opposite side of the main path up the rock, a side path leads to the Cobra Hood Cave, named for its uncanny resemblance to that snake’s head. The cave preserves traces of lime plaster, floral decoration and an inscription in Brahmi script on the ledge dating from the second century BC.

Follow the path up the hill behind the Cobra Hood Cave to reach the so-called Audience Hall. The wooden walls and roof have long since disappeared, but the impressively smooth floor, created by chiselling the top oft a single enormous boulder, remains, along with a five-metre-wide “throne”, also cut out of the solid rock. The hall is popularly claimed to have been Kassapa’s audience hall, though it’s more likely to have served a purely religious function, with the empty throne representing the Buddha; a rectangular cistern is carved out of another part of the same boulder. The small cave to one side of the Audience Hall retains colourful splashes of paint on its ceiling and is home to another throne, while a couple more thrones can be found carved into nearby rocks.

Return back to the main path from here and you should come out at “Boulder Arch no. 1” (as the sign calls it). Continuing through here, the main pathway – now a sequence of walled-in steps – begins to climb steeply through the Terrace Gardens, a series rubble-retaining brick and limestone terraces that stretch to the base of the rock itself, from where you get the first of an increasingly majestic sequence of views back down below.

The Sigiriya Damsels and the Mirror Wall

Shortly after reaching the base of the Sigiriya Rock Fortress, two incongruous metal spiral staircases lead to and from a sheltered cave in the sheer rock face that holds Sri Lanka’s most famous sequence of frescoes, popularly referred to as the Sigiriya Damsels (no flash photography).These busty beauties were painted in the fifth century and arc the only nonreligious paintings to have survived from ancient Sri Lanka; they’re now one of the island’s most iconic – and most relentlessly reproduced – images. Once described as the largest picture gallery in the world, it’s thought that these frescoes would originally have covered an area some 140 metres long by 40 metres high, though only 21 damsels now survive out of an original total of some five hundred (a number of paintings were destroyed by a vandal in 1967, while a few of the surviving pictures are roped off out of sight).The exact significance of tin1 paintings is unclear; they were originally thought to depict Kassapa’s consorts, though according to modern art historians the most convincing theory is that they are portraits of apsams (celestial nymphs), which would explain why they are shown from the waist up only, rising out of a cocoon of clouds. The portrayal of the damsels is strikingly naturalistic, showing them scattering petals and offering flowers and trays of fruit — similar in a style to the famous murals at the Ajantha Caves in India, and a world away from the much later murals at nearby Dambulla, with their stylized and minutely detailed religious tableaux. An endearingly human touch is added by the slips of the brush visible here and there: one damsel has three hands, while another sports three nipples. Just past the damsels, the pathway runs along the face of the rock, bounded on one side by the Mirror Wall. This was originally coated in highly polished plaster made from lime, egg white, beeswax and wild honey; sections of the original plaster survive and still retain a marvellous polished sheen. The wall is covered in graffiti, the oldest dating from the seventh century, in which early visitors recorded their impressions of Sigiriya and, especially, the nearby damsels even after the city was abandoned, Sigiriya continued to draw a steady stream of tourists curious to see the remains of Kassapa’s fabulous pleasure-dome. Taken together, the graffiti form a kind of early medieval visitors’ book, which give important insights into the development of the Singhalese language and script; some are also of considerable poetic merit.

Lion Platform

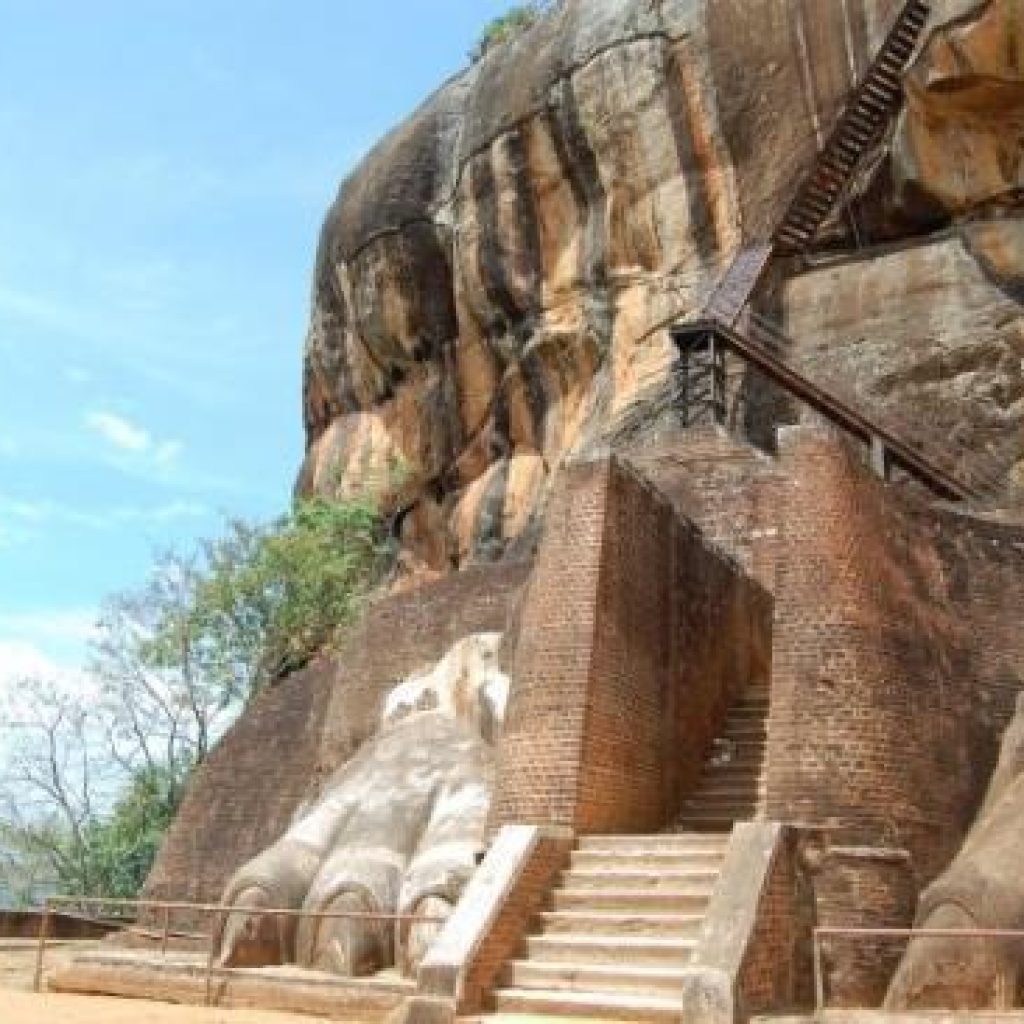

Continuing up the Sigiriya Rock Fortress, a flight of limestone steps climbs steeply up to the Lion Platform, a large spur projecting from the north side of the rock, just from here, a final staircase, its base flanked by two enormous paws carved out of the rock, leads up to all that remains of a gigantic lion statue – the final path to the summit apparently led directly into its mouth. Visitors to Kassapa were, one imagines, suitably impressed by this gigantic conceit and by the symbolism — lions were the most important emblem of Sinhalese royalty, and the beast’s size was presumably meant to reflect Kassapa’s prestige and buttress his questionable legitimacy to the throne.

The summit

After the tortuous path up, the summit seems huge. This was the site of Kassapa’s palace, and almost the entire area was originally covered with buildings. Only the foundations now remain, though, and it’s difficult to make much sense of it all – the main attraction here is the fabulous views down to the water gardens and out over the surrounding countryside. The summit shelves quite steeply; the king’s palace occupied the higher ground on the right, while the lower area to the left would have housed the living quarters of guards and servants. The two areas are divided by a wide, zigzagging paved walkway. The Royal Palace itself is now just a plain, square brick platform at the very highest point of the rock, next to which you can see a rectangular outline -popularly described as a “throne”. The upper section is enclosed by steep terraced walls, below which is a large tank cut out of the solid rock; it’s thought that water was channelled to the summit using an ingenious hydraulic system powered by windmills. Below here a series of four further terraces, perhaps originally gardens, tumble down to the lower edge of the summit above Sigiriya Wewa.

The path down takes you along a slightly different route — you should end up going right past the Cobra Hood Cave, if you missed it earlier, before exiting the site to the south.