Dambulla Cave Temples is acclaimed as the biggest and best preserved complex of Buddha images and rock paintings in South East Asia. Due to the importance of its historical contribution, the significance of its archaeological findings and the sublimity of its art, the Dambulla CaveTemples was declared as a UNESCO Heritage Site in 1991.

Lying at the heart of the Cultural Triangle of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, and Kandy, in the Central province of the Island, the Dambulla Rock rises from an elevation of 1,118ft from sea level to over 600ft and spans 2,000ft in length. It is 148 kilometres east of Colombo and two kilometres from the Dambulla town.

Upon arrival at the Dambulla Rock Temple the vista is dominated by a giant seated gold plated Buddha statue placed high over the newly built three storied Buddhist Museum. Unveiled in 2001 it occupies its position as a blessed sentinel overlooking the flatland that stretches for miles providing an uninterrupted view of the surroundings and casting protection on every living being below.

The stairway to the upper terrace of the rock where the fascinating caves await discovery is to the left of the Museum and begins in earnest. The steps appear easy at first but if you find the going too heavy, on to the left there is an alternate rocky reach to the base where the ascent itself is not arduous or steep but gradual, with a gentle gradient.

The panoramic view, as you climb higher, gets more astounding and breathtaking; it is said that, on a clear day, another world famed rock, the Citadel of Sigiriya, is visible on the landscape, 19 kilometres away.

Both these rocks have a common ancestor. They were formed by the combination of two great outcrops, each domical in shape and both are of importance in determining and chronicling the geological origins of Sri Lanka.

Reaching the rock’s upper terrace you face the Vahalkada, the formal entrance, which opens out to the paved courtyard with the Bo tree on the left. On the right are the five caves cloistered under a giant boulder protruding from the main rock and shielding it from nature’s elements.

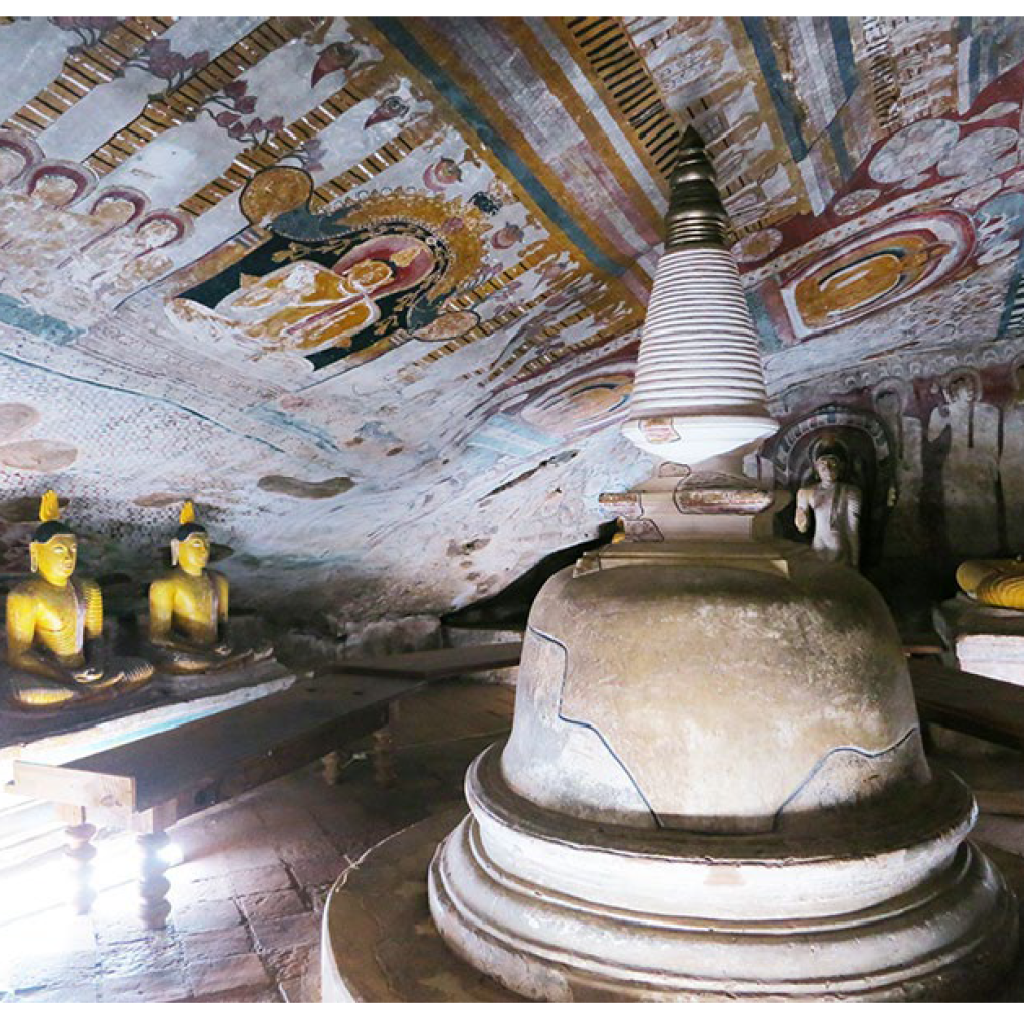

Though there are five caves in the Dambulla Rock Temple, in actual fact, it is one large cave containing an internal area of approximately 1,000 square metres. It extends from the rock face more than half way to the western slope. It is a deep excavated cavity, a vast cavern part natural, part tunnelled. It has screen walls and partitions creating separate chambers of which five are used as temples.

The first cave temple is known as the Devarajah Temple or the Temple of the King of the Gods. The large 45ft reclining Buddha is depicted in the state of Parinibbana or the Great Passing Away with a statue of Ananda Thero, the Buddha’s faithful disciple who recorded for posterity every sermon the Buddha preached, is found at the Buddha’s feet mourning the great teacher’s inevitable and natural demise. At the Buddha’s head is the statue of Vishnu; and myth holds that he used his divine powers as the King of the Divine Gods to create the cave complex.

The largest of these chambers—the second cave—is the architectural masterpiece, the Maharajah Lena or the Cave of the Great Kings. It has been formed by the addition of screen walls in the centre of the cavern. From east to the west it is 52 metres long and goes 23 metres into the rock and has a maximum height of seven metres to the main screen wall. Two large doors provide entry from a wide galleried verandah that stretches throughout the cave length. Its large interior has not been compartmentalised but an intricate arrangement of statues and paintings have served to differentiate it. In the eastern sector from the rocky ceiling, drops of water drip ceaselessly from a still unknown source within the rock’s ceiling. The water, believed to contain healing properties, is collected in a large pot and is used exclusively for the daily temple offerings.

In this rocky shrine, the centrepiece of the entire chain of caves, the principal image is the standing Buddha but the most awe-inspiring figure is that of the 30ft recumbent Buddha, hewed out of the rock, the elegant features of which are more aquiline than the others present. Behind this image, in the ambulatory, stands the sculpted image of King Nissanka Malla who in the 12th Century became the royal benefactor and restored the temple to its old glory, adding more images and gilding 50 of them including the main standing Buddha statue and commissioned more paintings to enhance the cave’s beauty. An elaborate inscription recording his contribution survives on the rock face. It comprises of 25 lines and is engraved on the rock in the temple courtyard near the Murage (Guard House) occupying an area of approximately six feet by four feet.

Seven metres above on the ceiling are the spellbinding murals of a 1,000 Buddhas. In the middle is the painting of the Buddha delivering his first sermon, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, attended by a host of celestial deities, when he first set the Wheel of Dhamma in motion. The paintings on the entire five cave ceilings cover an area of 2,000 square metres. Paintings of the Buddha’s life, his mother Mahamaya’s dream portending his advent and the conquest of Mara, transcending tawdry temptations thrust to thwart his avowed singular aim of attaining enlightenment, find their fitting place on the broad ceiling canvas.

Behind the principal standing Buddha image to which people pay daily homage with the offering of flowers; there are two of Lanka’s Guardian Deities Vishnu and Saman while painted on the rock are depictions of God Skanda also known as God Kataragama and God Ganesh. A row of Buddhas possibly depicting the Buddhas before Gautama, line the cave’s edge while a rock hewn small stupa, with eight seated Buddhas facing the eight zonal directions, is situated near the entrance where also a painted wooden statue of King Walagamba, stands silent guard watching over the artistic wonder he created in thankful worship.

The third cave temple the Maha Alut Vihara or the Great New Monastery is 90ft long and 85ft in width and is approximately 36ft high near the entrance. It is second only to the Maharajah Temple and was constructed by King Kirthi Sri Rajasinghe (1747-1782 AD) who introduced the Kandyan style of painting. A reclining Buddha statue of 30ft in length again takes pride of place for its length and beauty in this temple while a seated Buddha statue is crowned with a Makara Thorana or Dragon’s Arch above it. This granite statue is surrounded by 50 other Buddha statues and takes centre stage. The statue of the king attired in royal Kandyan wear stands at the extreme right of the temple between the reclining and the seated Buddha statues.

The fourth cave the Paccima Viharaya or the Cave of the Western Temple is 59ft long and 27ft wide and has, as its main image, a seated Buddha under a decorated Makara Thorana. Other similar Buddha statues surround the central figure. The cave also houses a small stupa, which is called Somawathi chaithya. Named after King Walagamba’s queen it was regarded as having contained her jewellery.

The final cave (fifth cave) was a later addition and is called the Devana Alut Viharaya or the Second New Temple. This fifth cave is 32ft in length and has 11 images of the Buddha in the standing, seated and reclining postures. Two of the seated statues depict the Buddha with the hooded cobra standing guard over his head protecting him from the rain. The picturesque tapestry of the Dambulla Cave Temples stretches back to the 3rd Century BC where, as new archaeological findings reveal, the rock had been the site of monastic life. From the upper terrace downward, on the western and southern slopes of the rock, 73 caves have been discovered and evidence that they had been used as cave residences by Buddhist monks has been unearthed.

The uppermost caves of Dambulla’s southern rock face played host to the throbbing artistic impulses of the nation and became the hub of art and culture, of religion and ritual, of trade and commerce and the gateway from the arid plains of the Dry Zone to the wetlands of the central mountain range. For over 22 Centuries its vibrant life continued unabated, even as it does now sans pause: thanks to a royal line of duty conscious Sri Lankan kings who, determined to keep the flame alive and not let it die out with the winds of time, felt it their beholden duty to write over the fading manuscript of history, the peeling palimpsest of its artistic canvas and restore its wondrous art once more to pristine glory, the rock caves of Dambulla still glow with the silent serenity of a thousand Buddhas.